Table of Contents

- introduction

- What is colour?

- Human visual perception of colour

- Colour space

- Chrome subsampling

- Visual comparison between YUV 4:4:4 and YUV 4:2:0

- Summary

introduction

Video compression is an essential component in the efficient transmission of high-quality visuals across constrained networks for all types of streaming media applications like video streaming ja heand remoting protocols. Reducing the size of (moving) images while maintaining as much visual fidelity as possible is essential for performance, scalability, and end-user experience.

Modern remoting protocols such as Citrix HDX, Microsoft RDP, Omnissa Blast and Dizzion Frame for example, rely heavily on video codecs like H.264/AVC, H.265/HEVC and AV1 to deliver responsive and visually accurate sessions over varying and sometimes challenging bandwidth conditions.

One of the most impactful techniques in video compression is chroma subsampling, which selectively reduces colour information while retaining full luminance detail. This method leverages a characteristic of the human visual system: sensitivity to brightness is significantly higher than sensitivity to colour. As a result, discarding colour resolution can dramatically reduce bandwidth usage with comparatively small perceptual impact.

This article provides a detailed exploration of chroma subsampling with a focus on YUV 4:2:0 and YUV 4:4:4, their relevance for remote graphics workloads, and their implementation in common codecs and image formats. The goal is to create a foundational understanding of how colour compression works, why it matters for remoting scenarios, and trade-offs between efficiency and fidelity.

What is colour?

Before diving into colour compression, it is helpful to understand how human vision works, and it is important to begin to explain some fundamental theory.

The first question to ask is a simple but essential one: What is colour?

Colour is the perceptual experience created when light reflects off objects, enters our eyes, and is processed by our visual system. Different wavelengths of light stimulate photoreceptors in our retinas to varying degrees, and our brain interprets these patterns as hues such as red, green, or blue. Colour is therefore not an inherent property of objects but a subjective interpretation produced by our sensory and neural systems. It is typically characterised by attributes such as hue, lightness, and saturation.

Hue refers to the basic colour category (such as red, blue, or green). Saturation describes how vivid or desaturated a colour appears, with low saturation shifting a colour more toward grey. Lightness (or value/brightness) describes how light or dark a colour appears and is influenced by the amount of luminance present.

In colour science, these perceptual properties have technical counterparts often used in imaging systems, particularly chroma and luma.

Chroma represents the colourfulness of a signal or image as relative to its brightness. It is closely related to saturation, though not completely identical to it; saturation is a perceptual attribute, while chroma is a measurable property. High chroma corresponds to intense colours, while low chroma corresponds to more neutral or muted colours.

Luma (Y′) is the weighted measure of perceived brightness used in digital video systems and is derived from gamma-corrected RGB components. Luma approximates human brightness perception and therefore aligns more closely with visual sensitivity than raw luminance.

Here it is important to note that our visual system is way more sensitive to variations in brightness (luminance/luma) than to variations in colour (chrominance). This difference strongly influences the design of image and video compression algorithms. Because we notice brightness detail much better than chroma detail, compression systems can safely reduce colour resolution while preserving nearly all of the perceived visual fidelity of the original image.

Human visual perception of colour

Now that we have an understanding of what colour is, the next question is: How does human vision work, and how do we actually perceive and interpret colour?

The human retina contains two types of photoreceptors—rods and cones—which convert incoming light into electrical signals that are transmitted to the brain via the optic nerve. These signals form the basis of all visual perception, including colour, brightness, motion, and detail.

Inside our eyes we have two different types of photoreceptors, rods and cones located in the retina, the light sensitive tissue at the back of our eyes, that enable us to see. They convert the incoming light into electrical signals that are transmitted to the brain via the optic nerve. These signals form the basis of all visual perception, including colour, brightness, motion, and detail.

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration PACE

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration PACE

The rods and cones have different functions. Cones are concentrated in the central part of the retina, especially within the fovea, where visual acuity is highest. They operate primarily under well-lit conditions and enable colour vision. There are three types of cones, each sensitive to different ranges of wavelengths corresponding roughly to long (L), medium (M), and short (S) wavelengths.

Rods, on the other hand, are distributed more widely across the peripheral part of the retina. They are far more sensitive to low light levels and support vision in dim conditions (scotopic vision), but they do not convey colour information. Rods are particularly effective at detecting motion and overall luminance contrast.

It is also important to understand that while the photoreceptor cones detect colour, the visual system’s neural processing places disproportionate emphasis on luminance for perceiving edges, fine textures, sharpness and contrast compared to colour information.

Research in visual neuroscience shows that the human eye can resolve luminance detail up to approximately 50 cycles per degree, whereas chrominance resolution typically peaks near 10 cycles per degree under favourable viewing conditions. “Cycles per degree” describes how many alternating light–dark (or colour–colour) patterns per degree of visual angle the eye can distinguish before they blur together.

In practical terms, this means that sharp boundaries, text, and most visual detail are perceived through luminance channels, while colour information is inherently lower-resolution in human perception. As a result, reductions in chroma detail often go unnoticed, whereas a reduction in luminance would appear immediately degraded.

The human eye can resolve luminance detail up to 50 cycles per degree, but chrominance typically caps out at around 10 cycles per degree. Here, the term “cycles per degree” is used to measure how well you can see details of an object separately without being blurry.

Compression algorithms, such as those used in remote display protocols, and image formats have used this fact for decades. By preserving high-resolution luminance information while reducing chroma resolution, they achieve substantial compression with minimal perceived loss in image quality.

Colour space

Before understanding chroma subsampling, it is important to understand the YUV colour space model, commonly used in modern image and video compression systems.

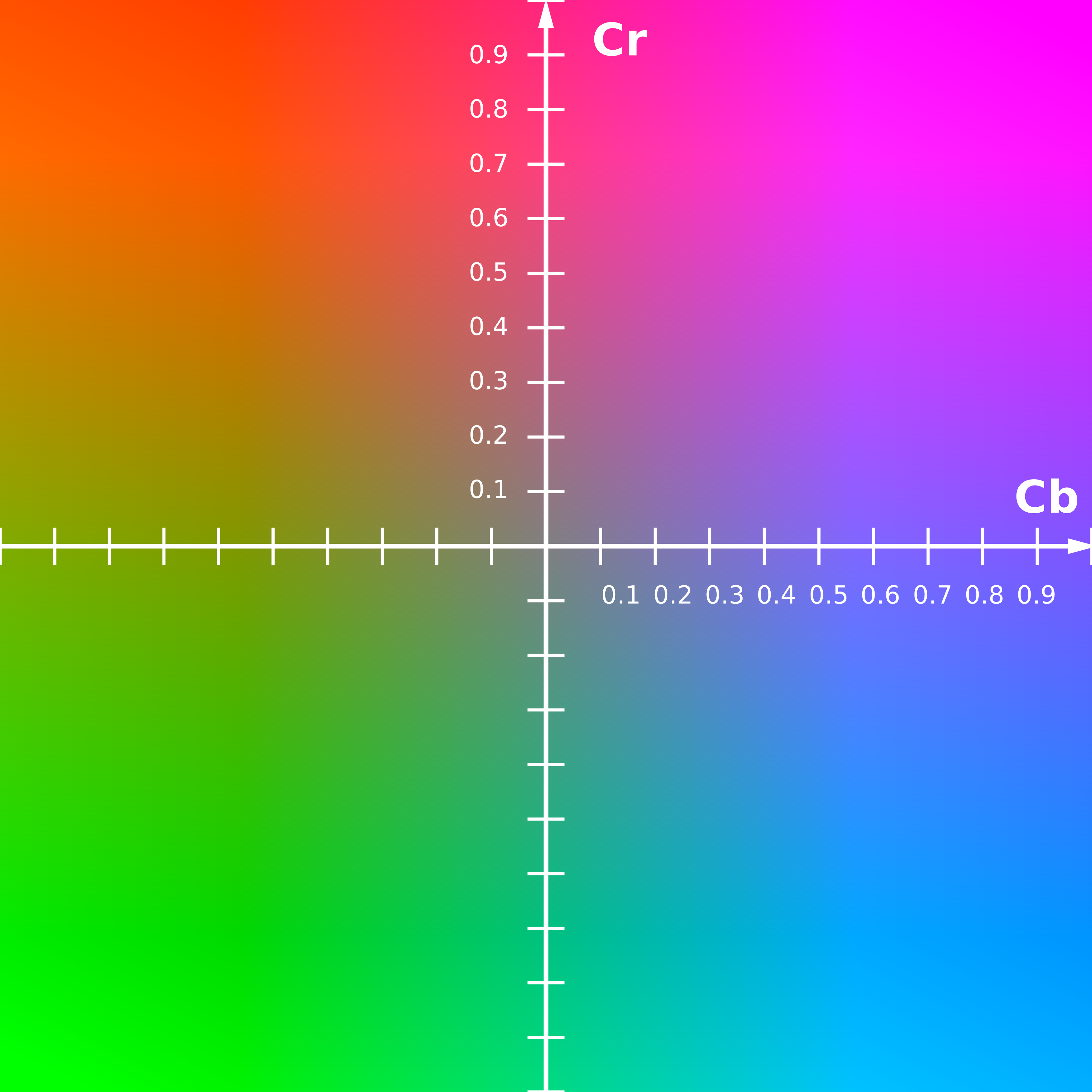

YUV, or more accurately referred to as Y′CbCr, is a colour encoding model that separates brightness from colour information. The Y′ component (also known as luma) represents perceptual brightness, while the Cb and Cr components (the chroma) represent blue-difference and red-difference chroma signals. Instead of storing absolute colour values, Cb and Cr encode how much blue or red is present relative to the luma component.

It is important to note that Cb and Cr are colour-difference channels, not full colour channels in the same sense as RGB. There is no separate channel for green because, mathematically, green can be reconstructed from the combination of Y′, Cb, and Cr. This works because the Y′ luma signal is calculated using a weighted sum of the red, green, and blue values, so once red and blue differences are known, the green component can be derived automatically.

Source: Wikipedia, The CbCr plane at constant luma Y′=0.5

Source: Wikipedia, The CbCr plane at constant luma Y′=0.5

Although YUV and Y′CbCr technically refer to different systems (YUV being an analogue colour encoding and Y′CbCr its digital counterpart), the two terms are used interchangeably in most modern contexts. For simplicity, this article will use the term YUV to refer to Y′CbCr-based digital video.

By separating luminance and chrominance, compression algorithms can encode each component according to its perceptual importance. Since the human visual system is far more sensitive to variations in brightness than in colour, reducing chroma resolution while maintaining full luma resolution preserves visual fidelity while significantly improving compression efficiency. This means that YUV can achieve such good compression very efficiently by reducing colour independently of brightness. In contrast, RGB represents each pixel with three full-resolution primary colour channels, Red, Green and Blue. While this provides excellent colour fidelity, it is less efficient for compression because the channels are highly interdependent and must be processed together. RGB images therefore require higher bandwidth and are more computationally demanding for compression algorithms compared to YUV-based formats.

Chrome subsampling

Chroma subsampling is a compression technique that reduces the amount of colour information, known as chroma, while preserving full brightness information, called luma. The luma channel is kept at full resolution, while the chroma channels are sampled less frequently.

The degree of chroma subsampling is expressed using the notation 4:a:b, which describes how many chroma samples are stored relative to luma samples in a reference area that is four pixels wide and two pixels high.

- 4, Represents 4 luma samples horizontally (the reference width)

- a, the number of chroma samples on the top row

- b, the number of chroma samples on the bottom row]

The first number, 4, represents four luma samples horizontally. The second number, a, indicates how many chroma samples are present on the top row of that region. The third number, b, indicates how many chroma samples are present on the second row.

When b = 0, as in 4:2:0, the chroma components have no samples in the second row; instead, the chroma values sampled in the first row are reused for the second row, effectively halving the chroma resolution vertically.

Two of the most common subsampling formats are YUV 4:4:4 and YUV 4:2:0.

YUV 4:4:4

In YUV 4:4:4, there is no subsampling at all. Every pixel carries its own complete set of Y, Cb, and Cr values. In practice, this means the colour resolution is identical to the brightness resolution, producing the highest possible fidelity.

ADD IMAGE

This provides the highest resolution of colour detail compared to YUV 4:2:0, but will result in larger images and increased bandwidth usage when used in video codecs.

YUV 4:2:0

With YUV 4:2:0 on the other hand, the chroma channels are sampled at half the resolution of the luma channel both horizontally and vertically.

In each 2×2 block of pixels, only a single Cb value and a single Cr value are stored. All four pixels share that chroma information, even though each pixel retains its own luma value.

ADD IMAGE

The result is that the chroma channels have only one quarter of the resolution of the luma channel. This arrangement significantly reduces the total amount of colour data that needs to be stored or transmitted.

This table shows the amount of samples for Luma and Chroma in a 2 x 2 pixel block:

ADD TABLE | Format | Y’ samples | Cb samples | Cr samples | total samples | | —— | ———- | ———- | ———- | ————–| | YUV 4:4:4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 12 | | YUV 4:2:0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

In YUV 4:2:0, each chroma channel (Cb and Cr) contains only one sample per 2×2 block, meaning the chroma resolution is one quarter that of full resolution. Because the luma channel remains unchanged while chroma is sampled at 25%, the overall number of samples in 4:2:0 is exactly half that of 4:4:4. This results in an approximate 50% reduction in both uncompressed image size and bandwidth requirements when using YUV 4:2:0 instead of YUV 4:4:4.

For example, if an uncompressed YUV 4:4:4 image or frame is 10 MB, the same image stored in YUV 4:2:0 format would be approximately 5 MB, assuming identical bit depth and no additional padding or packing.

Visual comparison between YUV 4:4:4 and YUV 4:2:0

The following image shows the difference between the two colour compression types, YUV 4:4:4 and YUV 4:2:0. From left to right, the first image is the uncompressed original, the second is encoded in YUV 4:4:4, and the third uses YUV 4:2:0 chroma subsampling.

ADD IMAGE

In this example, the image encoded using YUV 4:4:4 in the middle, looks almost identical to the one encoded in YUV 4:2:0, and both versions appear visually very close to the original uncompressed image. This is because the parts of the picture shown here rely much more on brightness detail than on colour information. For example, the textures in the fur are mostly described by the brightness channel, which both 4:4:4 and 4:2:0 preserve at full resolution.

The colourful background is mostly made up of smooth, soft colour transitions rather than sharp colour edges. These types of gradual colour changes do not require high-resolution colour sampling to look correct. Even when the colour data is reduced with YUV 4:2:0, our eyes do not notice this fact because we are far less sensitive to small changes in colour detail than we are to changes in brightness.

As a result, even though 4:2:0 stores only a quarter of the colour resolution compared to 4:4:4, the visual impact is minimal in examples like this. Most of us would not be able to tell the difference without zooming in or closer examination of the image. This is exactly why YUV 4:2:0 is so widely used: it can significantly reduce file size while maintaining an image that appears almost indistinguishable from higher-resolution colour formats in everyday viewing.

The comparison is more interesting when we look at different type of content below:

ADD IMAGE

This example is used to specifically highlight the differences between uncompressed colour data, YUV 4:4:4 encoding, and YUV 4:2:0 encoding when rendering complex text content with multiple colours and backgrounds.

From left to right, the first image is the uncompressed original, the second is encoded in YUV 4:4:4, and the third uses YUV 4:2:0 chroma subsampling.

Unlike the example above, which had smooth colour gradients and large areas of similar colour where chroma subsampling performs well, this example contains sharp, detailed text with many contrasting colours and small, precise colour areas. This kind of content exposes the weaknesses of chroma subsampling, particularly visible with YUV 4:2:0.

ADD IMAGE

With this example, by the nature of YUV 4:2:0, blurring, colour bleeding, and loss of sharpness in the coloured text and backgrounds, is notable. It is especially noticeable along edges and in areas where there are abrupt colour changes like the top row of text with the orange text on top of the green background. In general it is most noticeable around the text edges and coloured backgrounds.

This degradation of visual quality with YUV 4:2:0 is particularly impactful for remoting protocols, where text clarity is critical for usability and user experience. In these cases the chroma subsampling artifacts as shown above can potentially negatively impact the readability and lower the overall user experience.

Summary

Chroma subsampling plays a key role in how modern remoting protocols balance visual fidelity and bandwidth efficiency.

By using chroma subsampling as the default option, video codecs can deliver visually convincing results while significantly reducing bandwidth usage. This makes colour compression a crucial mechanism for remoting protocols, especially in bandwidth-constrained or latency-sensitive environments.

Understanding the differences between YUV 4:4:4 and YUV 4:2:0 is essential when evaluating the visual impact of subsampled versus non-subsampled compression:

YUV 4:4:4 preserves all colour information and is therefore better suited for scenarios demanding text clarity, UI sharpness, and detailed graphics.

YUV 4:2:0 reduces chroma data by halving colour resolution in both horizontal and vertical dimensions, offering significant bandwidth savings with minimal perceptual loss in many real-world use cases. This trade-off between efficiency and fidelity directly influences the behavior and performance of remoting protocols across diverse workloads.

While this article focuses on the fundamentals of colour perception, chroma subsampling, and the differences between 4:4:4 and 4:2:0, further analysis is required to quantify the visual impact. Metrics such as ΔE, SSIM, and PSNR will be employed in follow-up research to provide data-driven insights into how chroma subsampling affects remoting protocol performance.